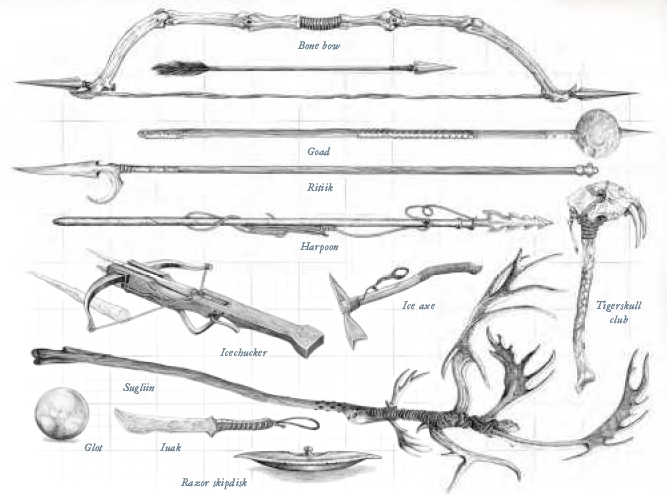

To those that don’t recognize it, the above picture was the cover art for an old D&D 3.5 supplement book, Frostburn. Frostburn was all things arctic for D&D. Avalanches of d6’s, chasms of frostfire, steeled swords forged from blue ice, fields of acid slush, and playable neanderthals were just some of the feature available.

I loved this book. Frostburn scratched several different itches for me. For one it was all things thing northern. Being from the South, I have what is probably an unwarranted romanticism for all things north – the landscapes, the weather, the feelings. I prefer grey days to clear ones, cold morning runs are my favorite, and snow, snow, snow. I suspect too that I’m not the only that fetishsizes the the north. Though there’s almost certainly more to it, it’s still interesting to note that the high watermark of World of Warcraft was in Northrend just as the best selling Elder Scrolls to date was Skyrim.

The other itch that Frostburn scratched for me goes back to the beginning. My first character ever was a druid, and my first game of D&D ever was an elaborate exercise in hunting/gathering – shuffling through my tackling box, picking locations to fly fish, selecting kindling for campfires. As odd as it seems in retrospect, I actually quite liked these experiences. And though I was clear-eyed enough to not get that granular, Frostburn was still the wilderness-survival campaign that I always wanted to run.

Frostburn does a quite a lot for wilderness-survival. There are charts for thin ice, snow blindness, traversing costs, and so on. Frostburn also categorizes existing terrain and severe weather, as well as introducing a slew of new phenomenon with great names such as: death hail, razor sleet and blood snow.1 Frostburn resurrects the rules for altitude sickness and hypothermia, as well as introducing a new system, cold protection, that does its darndest to try and conform with the existing (e.g Endure Elements) tools out there.

Frostburn was the campaign that I always wanted to run but never got quite to. There was some stuff I did later that was like Frostburn. For example, I ran a campaign in the far north that had an impending necromantic crisis (in retrospect I realize how much I might have plagiarized from Northrend), but anything I ran never seemed to be like the Frostburn that I had read about. So what happened? White whale syndrome? To some extent, sure. But for this campaign, and any others since, the biggest part that I’ve noticed to be missing is what Frostburn seemingly wants to emphasize most – the wintry danger – i.e the wilderness survival.

As described in the previous entry of Tabletop Syndrome, what undermines wilderness survival in Frostburn is what undermines inventory in general – magic. Frostburn does the best it can. As mentioned before it actually configures spells like Endure Elements into its cold protection system, but still there remain other spells that prove to be deeply problematic. Goodberry and Create Water both ruin any chances of extending survival into thirst and starvation, while Leomund’s Tiny Hut removes any possible dynamic associated with finding/constructing shelter. Even a measly cantrip such as Know Direction plays its own role in taking tension off the table. And this doesn’t even say anything of teleportation!

An argument can be made that these are just the perks of having a party (caster) that progresses in abilities, but especially as Frostburn is concerned, an alternative argument could be made that what should be happening isn’t that a system is slowly peeled away until it’s at first tedious, and then finally irrelevant, but rather it should grow more complex and dangerous as the adventurers get increasingly powerful. Dire weather strikes. Luckily the wizard’s Resilient Sphere can prolong what would have otherwise been a death sentence. But will the magic hold long enough for the ranger to scout out a permanent refuge?

Perhaps then it’s ironic that, despite everything I think on this subject, I’m right now putting the finishing touches on yet another Frostburn inspired setting. Like I said before, definitely a little white whale syndrome going on here. In my defense however, I have a few different factors going in my favor.

- Lower/adjusted expectations. For the most part I’ve given up on the wilderness-survival idea, given that I have both a druid and cleric in the party. Banning Goodberry seems cheap, especially when it’s been a campaign fixture,2 and taking away the ability to create water from a storm cleric seems worse than arbitrary. Mostly I am just hoping to break from the present adventure path, ditch its the end of the world-isms, and put some of the wild ideas that are in Frostburn into a giant snowy sandbox.

- No more Endure Elements. For some mysterious purpose, 5e has cut endure elements out. The reason I suspect has nothing to do with wilderness-survival, and in fact, is probably for the opposite purposes of minimizing environmental effects. In any case it’s an accidental win for my campaign, which can now operate with a heat/fuel system.

- My players are bean counters. While I questioned in the previous entry whether pen and paper is the best format for bookkeeping, or whether even most groups would want anything to do with bookkeeping, my present group (or at least the majority) is the exception to my own rule. The wizard in particular loves the deliberation of such an approach, and as such there is reliably half an hour’s worth of debate before any potential combat whatsoever. A good two thirds of encounters in my sessions are circumvented by other creative, which as far as I’m concerned is fantastic.

Back to the original point though, the heat/fuel system works less like Frostburn’s cold protection system and more like a finite amount of provisions to keep track of. I am normally not a fan of giving players (and myself) something extra to keep track of, but given these players, it’s something I’m willing to experiment with.

Will the wizard eventually render this experiment obsolete? Yes and that’s fine. That’s a part of adjusting expectations. The real solution of course would be to adopt another system that actually embraces the wilderness-survival, or to overhaul the existing one. But even if this group would be more inclined to it than others, these just aren’t the circumstances in which we met. D&D pulls strangers together. [Insert indie title] does not. Perhaps the hopeful thought to hold on to would be to reason that with sufficient time, we could wrap up this campaign, gain newfound trust/ambition, then switch to that gritty inventory heavy system after all to finally achieve the dream that I first found in Frostburn.

Would this actually be a good idea however? Or is all this effort exerted in the service of something that is better left imagined than implemented? My own fear is that, as RPGs are concerned, white whales are not limited to the sea.

1: An honorable mention goes to Fairie Frost. What sounds quite gay (frivolous) at first is actually fairly unnerving. Taken from Frostburn:

…faerie frost resembles an ice sheet with a faint rosy hue. It costs 2 squares of movement to enter a square covered by faerie frost, and the DC of Balance and Tumble checks increases by 5. A DC 10 Balance check is required to run or charge across faerie frost. Creatures who remain in a region of faerie frost for 1 minute or more become subject to its deadly hallucinatory curse, and must succeed on a DC 18 Will save or become dazed. This is a mind-affecting compulsion effect. Creatures that succeed on this save are immune to the effect of that patch of faerie frost for 24 hours. Dazed creatures remain so indefinitely, but are entitled to a new Will save once per hour to break free of the faerie frost’s effects. While under the curse’s effect, ensnared characters experience euphoric delusions of warm temperatures and inviting flowery meadows. These characters often sit or lie down on the ice. They remain subject to the normal effects of cold or other existing conditions, remaining completely oblivious as they slowly freeze to death. Characters who remain in a patch of faerie frost for 24 hours must succeed on a DC 18 Fortitude save or turn to ice (as the spell flesh to ice). If a character succeeds on this save, he must make a new Fortitude save once per additional hour (DC 18, + 1 per previous attempt). Spotting faerie frost requires a DC 20 Survival check.

2: Once the party came upon a hill giant crossing that was taking food for a toll. The voracity of hill giants is of course well known, so travelers were being compelled to offer livestock, bushels of crops, untold pounds of flour, etc. It was then that the druid offered the giants goodberries. How filling is one goodberry? The language in 5e states, “Eating a berry restores 1 hit point, and the berry provides enough nourishment to sustain a creature for one day.” It can be argued in other words that one casting of Goodberry can feed anything from a mouse to a Tarrasque – assuming the later even needs “sustaining.”

The common sense ruling is of course to put a size restriction (medium), but finding this oversight hilarious, I instead opted for an interpretation that rules that giants of any size can indeed be sustained by a single goodberry a day, and further that they quite like goodberries and will take a liking to you like a dog that you have fed only one dog treat to. It’s been a recurring problem since.